We all live in the Vampire Castle now

Revisiting Mark Fisher's essay.

I’ve been working on something about the politics of the internet — about how structural forces built into this technology have worked to pacify people and have foreclosed on the possibility of a political movement…by turning everything into entertainment. The essay has grown in size and has gone into all sorts of directions, so I’m gonna break it up into a few smaller pieces that I’ll publish over the next two weeks.

To start, I want to bring back Mark Fisher’s infamous essay “Exiting the Vampire Castle.”

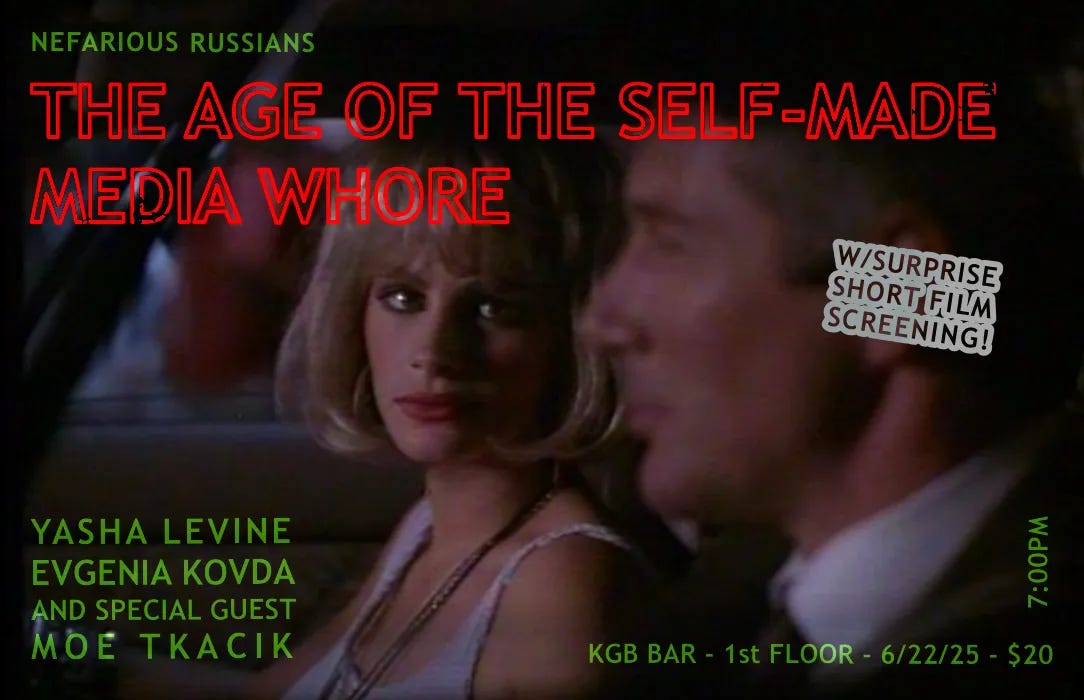

We’re doing a live event in NYC later this month on the sad state of our media: JOURNALISM IS DEAD. WELCOME TO THE AGE OF THE SELF-MADE MEDIA WHORE. Get your tickets today!

It has been almost twelve years now since he wrote this essay — which was about a toxic and destructive political culture that had appeared in left-liberal circles on the back of social media technologies. One of the core traits of this new formation was to viciously attack people inside your own camp — to strip down and cancel people for some perceived transgression…for saying the wrong thing, for not being pure enough, for having too much privilege. As Fisher pointed out, the people engaged in this new politics were usually atomized and lacked any connections to each other in the real world. Instead, their in-group identity was built around virtue signaling and online gang-stalking mobs and spectacle. It was all about tearing people down — a kind of macabre entertainment in the ignorant and malicious mob justice against people who were or could have been comrades, people who were on “your side.” Fisher was deeply depressed by the emergence of this toxic culture and that he considered exiting politics altogether. To him this wasn’t politics; it was anti-politics. Two years later, he killed himself.

Fisher’s essay ended up being very formative to a lot of people on the American left who were just coming of age in the Obama years and Occupy Wall Street. People inside the DSA and the Bernie Movement reread his essay and took what Fisher wrote to heart: You can’t build a political movement if you’re constantly policing each other for perceived micro-aggressions and canceling each other for stupid or offensive things you said online. Politics is about trying to work together — it’s about talking to people and finding things you have in common with each other. To build a left movement, you need to focus on material issues that matter to people. It was this basic truth that Fisher pinpointed so very well, and it served as a guiding light to a totally depoliticized generation being raised on memes and flame wars.

You could say that the Vampire Castle essay became the equivalent of the Communist Manifesto to a big chunk of the Bernie Movement, and a lot of people tuned their social media messaging to reflect Fisher’s critique: They tried to drop identity politics and focused on core class issues that mattered to most Americans: wages, work conditions, cost of living, healthcare… And that was good. But looking back on it now, I think both Fisher and the left that he inspired avoided dealing with a much bigger issue that was only hinted at but loudly implied in his essay: it wasn’t just about communication styles or approaches to organizing, the problem he was critiquing was built into the politics of internet technologies themselves.

In the Vampire Castle, Mark Fisher focused on online left-liberal politics — specifically how toxic identity politics were being used to destroy the left. But I think the Vampire Castle is bigger than just the left. All politics in our world have become trapped in the Vampire Castle — trapped in endless culture wars where everyone is constantly pitted against each other in an endless fight that involves constantly evolving identity politics, fringe causes, peripheral issues, and perceived slights. All of it addictive and destructive. All of it preventing us from coming together.

Fisher didn’t focus on the politics of the technology that created the Vampire Castle. But those technological politics are there. That’s because the Vampire Castle was built on social media, and social media has been engineered to create and multiply conflict, to trigger anger, to create division and strife, and ultimately to control and pacify us by getting us addicted to online interactions. That’s how these giant monopolies make money, it’s how they keep us on their platforms.

This kind of virtual sociality has become central to our political culture. The social media platform is where most of our politics and our political interactions take place. I mean, hell, the President of the United States is addicted to social media and has his own social media platform. And his former buddy Elon Musk, the richest person in the world, is also addicted to social media and bought a platform to promote his ideas. Now they’re ridiculously dueling with each other from the safety of their own social media castles. So, yeah, social media is central to politics. From the lowliest peon to the mightiest capitalist — we all live in it and are affected by it, shaped by it.

It’s true that social media did not invent political infighting and petty conflict. But the internet has allowed it to be pushed on us on an unprecedented scale. We’re bombarded by culture war slop 24/7 — it’s tuned specifically to our interests and it comes at us when we don’t want it: when we’re commuting to work, while we’re on the toilet, while we are hanging out on a playground with our kids, when we just want to check our email….

If you take a step back and look at it coldly, like a future historian studying us 200 years from now would, it would be very clear that these systems were designed to have us at each other’s throats — designed to preemptively smother any attempt of people coming together. And in fact you don’t have to be a future historian to see the trends. In my book Surveillance Valley I told the forgotten history of how the internet was born out of the Pentagon’s pacification efforts during the Vietnam War. And the more I look at the internet today, the more convinced I am that the pacification dimension of this technology is still with us today — and that it is even more powerful than anything that America’s technocratic planners envisioned a half-century ago, when they were building out the early internet and crunching surveillance files on Thai hill tribes, Vietnamese peasants, and American antiwar protesters.

To bring it back to Mark Fisher…

Yeah, our culture of petty political conflict and division is a problem. But this culture doesn’t exist in a vacuum. This culture has been shaped and influenced by internet technology. We never asked for this tech, and yet it was foisted on us. It has reorganized our culture and politics and our world, and little can change as long as we’re plugged into it.

I’ve become convinced that we can’t exit the Vampire Castle without physically exiting the technology out of which it was built. We have to realize that technology has a politics of its own, and we can’t ever fully escape its politics as long as we live within the technology, engrossed in our phones. Thinking you can win from within the Vampire Castle is what entraps you even more — it’s what makes it a Vampire Castle.

To be continued…

—Yasha

Read next:

PS: Exiting the Vampire Castle is why we have decided to start regularly doing events in the real world — not just to entertain and inform but to bring people off these demonic platforms and to connect us to each other in real life. So come to our next event in NYC. We’ll show a surprise short film by Evgenia, talk about the death of journalism, and hang out. Sunday, June 22.

I'm getting the feeling that in a few years the internet will be so polluted, dysfunctional, and surveillance-ridden that it becomes uncool and people (except boomers, not sure about Gen Z) will start turning to experiences in real life more. Eventually the perception will be that the internet is like being hunched over slot machines at the casino, and a place for old people to be scammed, lied to, and yell at each other. The real and tangible becomes valuable when this technology becomes so burnt out, toxic, and lame that any alternative, especially those less ephemeral or public, seem more enjoyable.

The internet and AI just may be cultural amplifiers Neither of these technologies mediate conflict, instead each accelerates it.

200 to 300 years ago Hobbes and Hume seemed to agree on the assumption that our reason serves as a scout for our passions. Along with such passion/emotion in 2025 are emotional impulses continually stoked by the internet that appears not simply to be satisfied with winning but also seems quite comfortable with attempted destruction of opponents.

As the brilliant Nazi opportunist Carl Schmitt recognized in the 1920s politics has little to do with the state and much more to do with the intensity of conflict between designated "friends and enemies."