Thinking about Soviet films on Victory Day

Yesterday was the 80th anniversary of victory over Nazi Germany. As most people in the world (but only some Americans) know, it was a Soviet victory over Nazi Germany — a victory with a loss of over 20 million Soviet people. It has been the central holiday in Russia, besides the New Year, ever since — even after the collapse of the USSR, when I was growing up. So it was always a big deal. But the level of festivities and grandiosity of the military parade this year feels to me unprecedented. The narrative of the parade is not just about WWII any more. Victory Day has become a symbol for a bigger struggle against the “collective West” — not just in the form of what’s going on in Ukraine but as part of a larger, more expansive effort to defend the motherland from enemies that seek to destroy it going back into the mists of time.

While this kind of thinking shocked me at first when it started over three year ago with the “special military operation,” now it doesn’t even seem that crazy. It rings somewhat true. Yet there is a big blind spot in this rhetoric that tries to establish continuity between the Russia of today, the Russia that won WWII, and the eternal historic Russia. The blind spot is communism. The rhetoric omits any mention of it. It wasn’t a historic Russia that won it WWII and that built much of modern Russian society — it was Soviet Russia and the larger Soviet Union. But communism — what people were fighting for when they were fighting the Nazis — isn’t mentioned, except in passing as symbols on a flag.

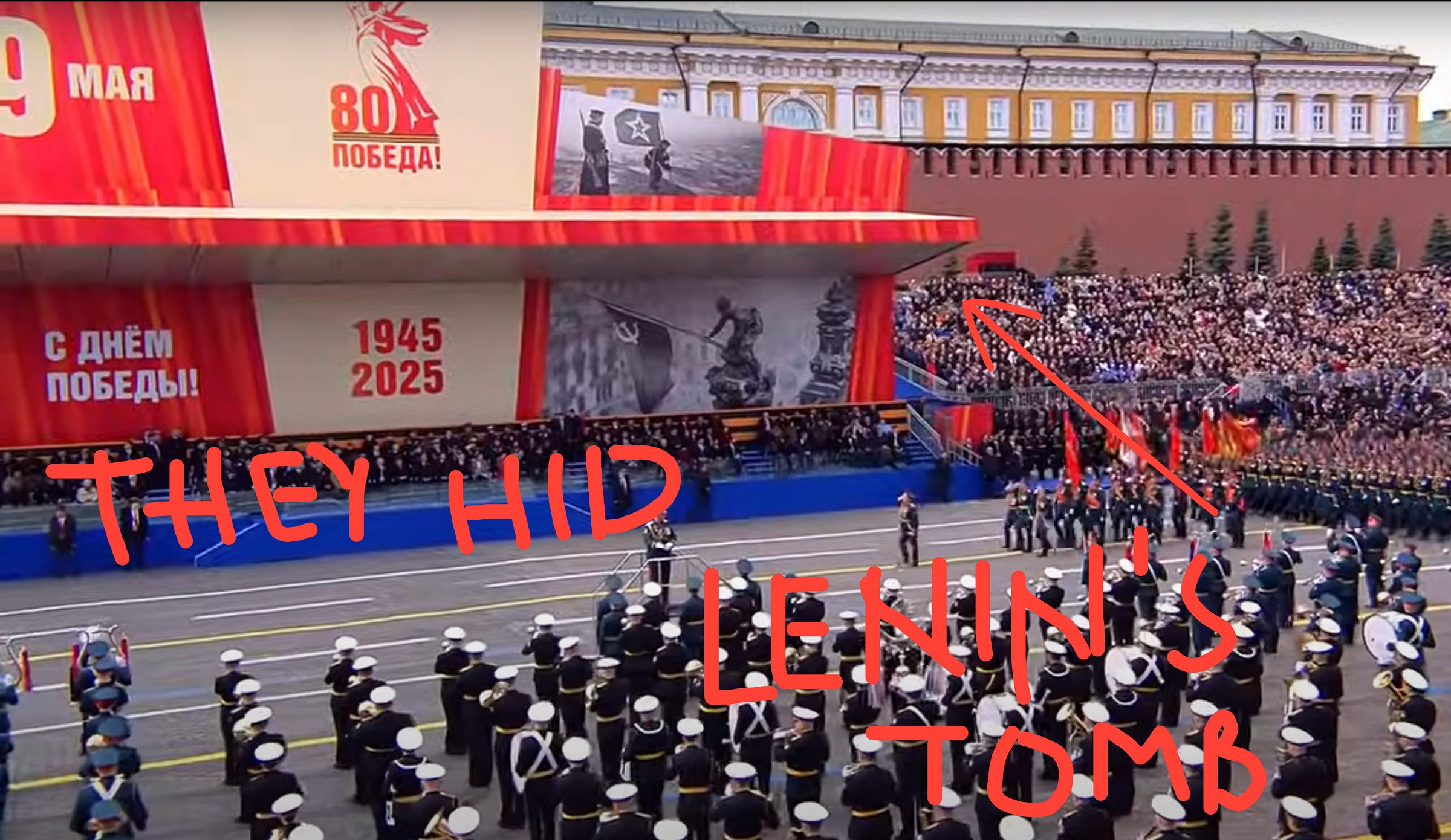

There has been a full capitalist restoration in Russia. Putin is not an heir to Lenin or Stalin. And in fact Lenin’s Tomb, which sits so prominently on the Red Square, was fully covered by posters and hidden from public view during the victory parade. So while there is still a photo of a Soviet flag with its hammer and sickle on the Reichstag everything else USSR-related seems to be buried and erased. Essentially, they put Lenin behind the curtain — hid him in the closet.

All that aside, I actually just wanted to write about and recommend a great and little-known WWII movie for you to watch — Ascent by Larisa Shepitko. It won the Golden Bear in 1977 at the Berlin Film Festival. Since then it was definitely surpassed in fame by another WWII film by her husband Elem Klimov, Come And See. I watched it again a few years ago at a sold out screening at the Egyptian Theater in Los Angeles. And yes, it is powerful, but Ascent deserves to be known too.

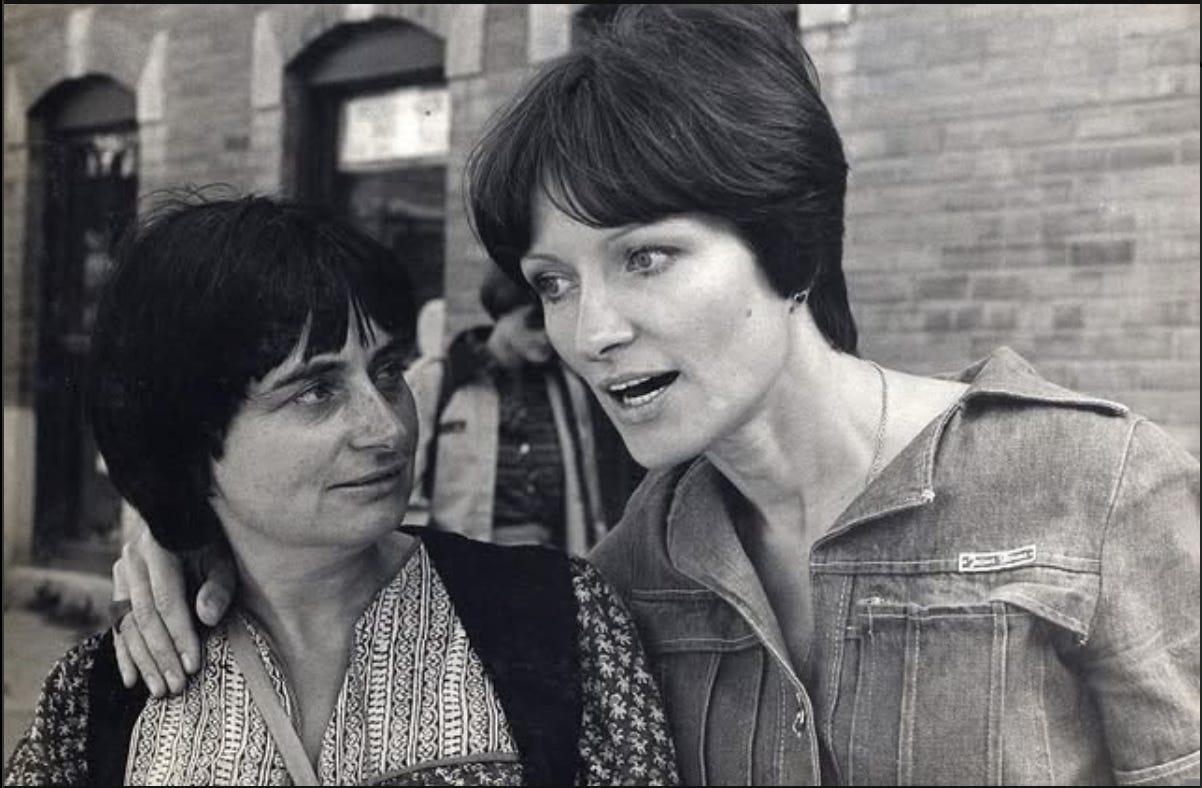

Larissa Shepitko was one of the great Soviet directors of her generation along Tarkovsky, Paradzhanov, Klimov. Today she is referred to as Ukrainian director, since she was born in eastern Ukraine. But back in the day she called herself just a Soviet artist.

Larissa was one of the first celebrated female filmmakers. She got into the Moscow Film School very young, right after high school, and studied under Alexander Dovzhenko. She met Elem Klimov there and eventually they got married but kept working separately on their own films while raising their son. Already this sounds pretty utopian and out of reach for American women in 1960s. Larisa was also an old Hollywood beauty like Charlotte Rampling (Klimov called her my Goddess) and many were surprised that she preferred directing to acting. But that was her calling and she was great at it. She was called in the filmmaking community “Iron Wind” for her ability to overcome all obstacle and realize her vision. It is interesting that she wasn’t a feminist — that term didn’t exist in USSR — and maybe she didn’t need the concept, because she was a “comrade.” In the USSR women had all the equal rights to men since 1917 — which makes America seem so backwards.

In one of the interviews available on the Criterion Channel Larisa said that “she doesn’t believe in male and female cinema, only in serious and sentimental one. And many male directors are known to produce ladylike sentimental films.” She believed that “women, while being an equal half of what is our human nature, can share amazing things with the world. That men are not capable to grasp certain phenomena in the psyche of human beings on such a deep intuitive way that women can.” I agree with Larisa and her words not only ring true but seem avant-garde in comparison to often open ghettoization of female filmmakers in the US that is sold as a victory — yay women make movies about women, have their own festivals, workshops. The slogan goes something like “Support women and other minorities” it feels as if we are in the 1950s. Women are not a minority! It’s offensive.

Criterion Channel has a few of her movies including Ascent which is her magnum opus and the last film. She died in the car crash two years later while making another film. Elem Klimov got hired to finish it for her and he went to the film set a week after her death. That’s how committed he was to the work that mattered so much to her.

Watching Ascent made me think of Katheryn Bigelow, pretty much the only American female filmmaker working in the war film genre and who is accepted as “one of the boys”. Ascent is nothing like Hurt Locker — a rather crude film that attempts to humanize and glorify a patriotic soldier in useless war in Iraq, an imperial war. Ascent is different. It is based on a story by Vasil Bykov, a Red Army lieutenant and writer. It is about two Soviet partisans who get captured by the Nazis and it shows what choices they make and how it affects them spiritually. It is a deeply existential film that asks: what is betrayal? It wonders if there is anything beyond…anything more important than this physical existence in your body that is worth sacrificing yourself for? Larisa does say with this film that, “Yes. There is.” Ostensibly it’s a patriotic communist film about a heroic partisan, but Larisa used Jesus as the reference to cast the main character Sotnikov, the one who chooses torture and execution and doesn’t betray his comrades. This is a film about sacrificing yourself for a worthy cause greater than yourself. And it shows how the other captured partisan Rybak after saving himself by betraying and giving away his comrades realizes that he betrayed himself too and he is a living deadman. He becomes a Nazi collaborator and has nowhere to run away anymore as he initially planned. So the initial compromise he made out of fear and thought was a small and forgivable one, changes him and his life forever.

The experience of making this film made Larisa religious which was not appropriate for a Soviet artist. Yet now watching it I think she actually got to the truth of communism more than the propagandistic run-of-the-mill Soviet filmmakers that eschewed any metaphysics as “ideologically reactionary.”

This attitude connects Larisa to her husband Elem, who picked the title Come and See after a line from the bible. It also connects her to Tarkovsky, whose movies contain the harshest critique of the narrow mindedness and hubris of Soviet technocratic ideologues, who with their crude dialectic materialism deny people access to sublime, to feel like there is something bigger than them, and yet force them to believe in a future communist society, a paradise on earth, a project that they were expected to devote their life to and to be stoic about it and not complain about the sacrifices they have to make. Stalker and Solaris were really about this blind spot in Soviet positivism.

With censors recognizing the Jesus motif in the film, Ascent was almost “shelved” — denied distribution, which was how films were censored in USSR. You were often allowed to make your film, but there was a chances that no one would see it if it was deemed ideologically dubious. But then a war hero, a former partisan, praised Ascent and gave a long celebratory speech after its premier, and the bureaucrats had little choice but to allow it.

I think it’s a very timely movie considering all the wars that are going on today. It made me think if a similar movie could be made today than only a Palestinian filmmaker could make one. The truth is on their side.

—Evgenia