Sergei Eisenstein vs Hollywood

When Russian artists had self-respect

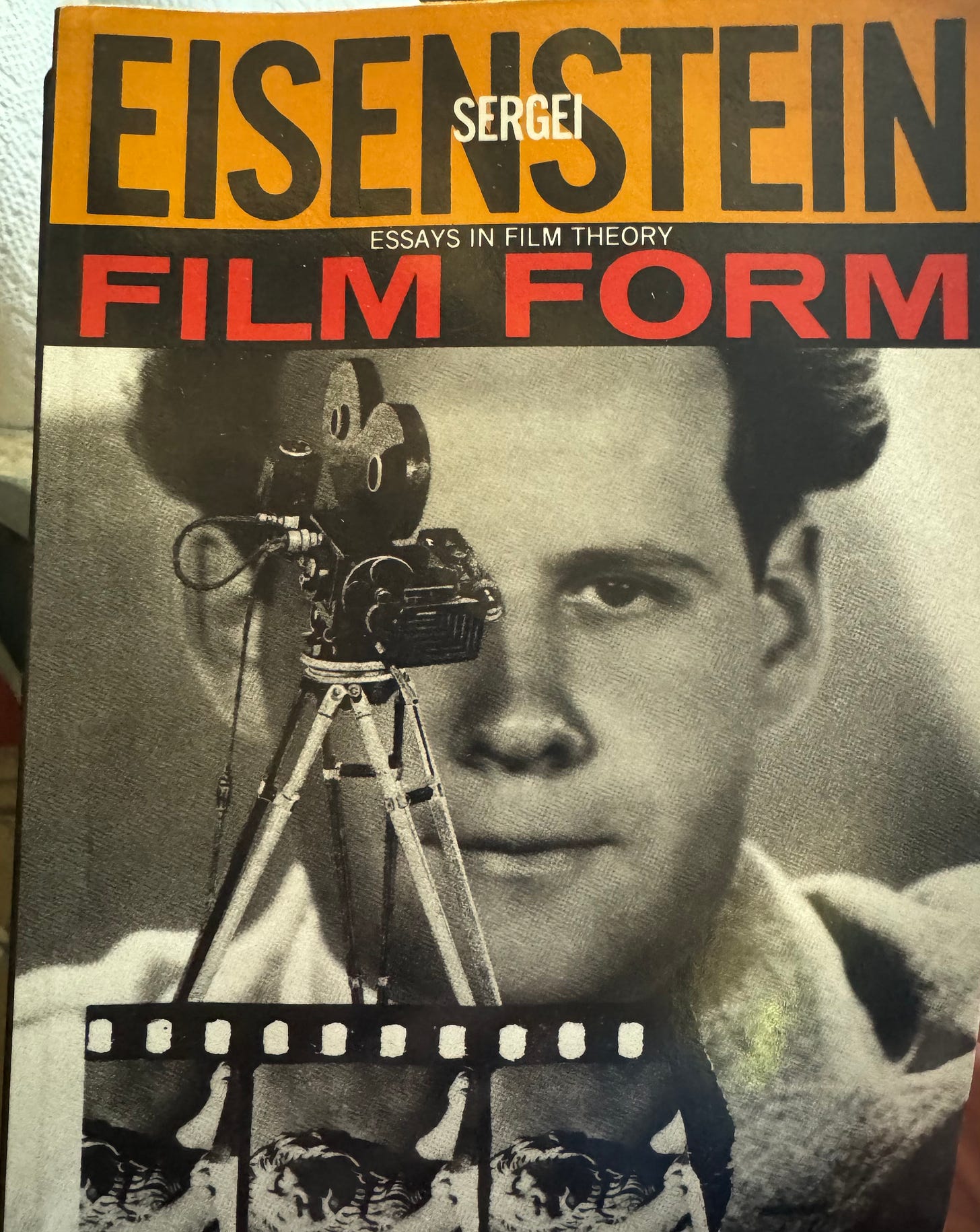

I’ve been going through my books yesterday — I have too many and we have to start packing in preparation for our move back to NYC. I picked up a collection of essays on film by Sergey Eisenstein and started reading one of his lectures on film treatment — a lecture he prepared for his students in VGIK, the famous Soviet film school — and I couldn’t put the book down. The confidence this man had is a confidence and vigor of a revolutionary man, a man who sees himself on the right side of history. He quotes Engels and Lenin along with Shklovksy, Joyce, Dumas, and Dickens. He switches between various subjects — going from the technical craft of filmmaking to the psychological and philosophical underpinnings of cinema with ease and knowledge you rarely encounter today among filmmakers anywhere. He is a real renaissance man who is passionate about cinema’s promise as the youngest and the most powerful art form — the most important art form, too, as Lenin famously said.

Eisenstein was lucky to die young at 50 in 1948 and didn’t get to live through the debunking of Stalinism, the unraveling of the Soviet myth, and the ultimate demise of the entire project. He lived through the most vital period of the Soviet Union — and thus his experience of Russian culture was very different from mine. He was proud of his culture, and very hopeful. And his single-minded belief in the revolution gave his films a real charge — the way it did to Mayakovsky’s poetry, as well. (Mayakovsky died in a timely way, too. He shot himself in 1930 at the peak of his poetic fame.)

Eisenstein was one of those rare men who got to live and work in those times when the Soviet Union was at the avant-garde of history, when it represented the future that other countries only could dream of. So his supreme confidence and even arrogance is understandable. He saw Soviet citizens revolutionizing the film form, inventing modern cinema. He taught at VGIK, the Moscow film school, the first and oldest film school in the world founded in 1919, so he had the right to feel that way. Beckett, before he fully committed to writing, tried contacting Eisenstein because he wanted to move to Moscow to study at VGIK. It’s so hard to believe now.

When I was growing up VGIK was not avant-garde any more. It was uncool, old and irrelevant. And a family friend my age — the great grandson of Victor Shklovsky — went to study there cinematography and dropped out after a semester because it was lame and barely functional.

Anyway, back to Eisenstein and Moscow’s glory days. In his essay on film treatment, he tells a story of his involvement with Paramount pictures. In the 1920s he was hired to make an adaptation of the novel American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser. I don’t know if Americans read him these days, but he was huge in Soviet Union and I read him when I was 15, since I found his books in my home library. Dreiser was a fellow traveler and his work was translated and widely promoted in USSR. But he was big back home in America as well, so Paramount wanted to cash in and make this film and went to Eisenstein to do it. The problem, Eisenstein writes, is that his treatment of the story was rejected, even though Dreiser himself loved it. It was considered too Marxist, too deterministic.

American Tragedy is based on a true story, a murder of a working girl in upstate New York. In the book the main character Clyde Griffiths, a supervisor at his wealthy’s uncle shirt collar’s factory, seduces a poor girl toiling there, gets her knocked up and decides to kill her her to escape having to marry her and thus ruin his prospects in life, which included marrying a daughter of another factory owner who is interested in him. Clyde plans to take this girl on a boat ride and then to overturn it so she would drown, as she can’t swim. But when they are on the boat he doesn’t want to do it anymore. He doesn’t have it in him, and has a change of heart. But the boat overturns on its own anyway, and the girl does drown. It all seems a fait accompli. So he swims away and leaves the girl there. But later he gets caught and prosecuted.

It’s a complicated long psychological novel that shows how the capitalism mode of production drives people towards crime and inhumanity. Eisenstein focused on that in his script for the film and Paramount didn’t like it at all. The studio head Shulberg asked Eisenstein if he thought Clyde was guilty. “No,” said Sergei. “But then your script is a monstrous challenge to American society,” Shulberg responded.