Influencerism is the highest form of capitalist realism

A political manifesto from mid political influencer Yasha Levine.

In the early 1990s, when the internet started hitting the consumer market in America, I was a Soviet immigrant kid in middle school in San Francisco. After school, I’d hit Yahoo and click over to the adult section, where I’d spend half an hour listening to pings and screeches while downloading photo sets of mostly soft-core porn. I was just a kid, and this technology seemed normal to me. Interesting but otherwise unremarkable and pretty boring, too. I can’t say the newness of it was something that was apparent to me. Everything was new to me — I was living in a new country, speaking a new language. So I took the sudden appearance of the internet as just another new thing in a new environment. I definitely wasn’t aware that a lot of people in America — many of them within a 40-mile radius of where I lived — were talking about this tech in religious terms. Not that I, a kid of an atheist state, would even know what “religious” meant.

Anyway, I found out later — particularly when I was writing Surveillance Valley — that America’s media ecosystem at the time had been filled with a messianic fervor. There were utopian proclamations about a coming revolution. The internet and the personal computer were going to change everything. They would move the world in the direction of democracy and egalitarianism and limitless wealth. An unstoppable wave was about to rip through the world and wash away bureaucracies, governments, business monopolies, and militaries, clearing the way for a new global society that was more prosperous and freer in every possible way. This was the mainstream position. The kind of stuff you’d read in Wall Street op-eds. As we all know now, it didn’t work out that way. No matter what part of society the internet touched, it ended up concentrating political and economic power, spawning a new oligarchic class, and creating a pervasive system of surveillance and control. And yet this old-school internet utopianism refuses to die. From AI to self-driving cars to Substack, lots of people still want to believe in the dream.

I wrote recently about the Substack Utopianism I’ve been seeing on here — about how there is a certain crew that’s pushing Substack as some kind of anti-establishment platform that will help cure the ills of American media. Today I want to address another dimension of this Platform Utopianism, our ongoing belief in the power of politics by app. It has to do with this: It’s true that technologies like Substack — but also Patreon and YouTube and other services that allow direct monetization of cultural and political media — have allowed people to bypass traditional media structures to reach big audiences and make money, sometimes huge amounts of money. In this new world, older, more traditional power structures play a smaller role, and things are more democratic. People rise up and go viral more on the pure strength of their talents. It seems more meritocratic. And it is in a way. But these technologies, while they have thrown off the old masters, have acquired a new one. And this new master is harder to see. It’s not a person who tells you what you can and cannot do. The new master doing the talking is a market force — nudging, pushing, rewarding, penalizing… On the surface, these new platforms have shaken up the way the media operates, made it more democratic. But deeper down, in reality, what they have done instead is to bring the media — and the people who produce it — closer in line with market forces. In that sense, they’re just another manifestation of the slow grind of neoliberalism — bringing everything into the market, commodifying every little bit of human life that hasn’t been commodified yet.

Let me try to explain what I mean by starting with a personal story and a few observations about the state of our media today.

My direct-to-consumer journalism journey started in earnest about five years ago during the lockdowns when I began posting in a real way on Substack.

Evgenia and I had just moved back to LA from NYC because I was in the process of selling a documentary series based on Surveillance Valley — aiming at one of the big streaming networks. Everything was going according to plan, but then COVID hit. Hollywood stalled, producers started freaking out, projects got abandoned, and my own show was a victim of that whole thing. So there we were — stuck in LA in a place we were temporarily subletting from a friend of a friend, the two of us isolated from everyone, with no job, future prospects uncertain, worried about catching the virus and dying. We were all characters in Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year— except we had Twitter and Facebook and…Substacks.

Everyone talks about how shitty that time under COVID restrictions was — with many basing their entire political identity on opposing anything like that from happening again. But to me it was kinda nice. I had become used to my literary ventures flaming out, so I wasn’t that surprised or shocked that the Surveillance Valley show was cooked. And I was enjoying the lockdown. The suspension of normal life in those days was actually quite pleasant, and it made me even kind of hopeful about the future. There was the fear and the death and control, sure. But there was an optimism, too. The pandemic, at least at first, put the brakes on our consumerist rat race. Many more people had time on their hands to hang out, to cook, to think about the world, and to experience their lives outside the never-ending bullshit jobs cycle. I thought that maybe something positive would emerge, that the status quo would get shaken up. I know I wasn’t the only one who felt this way. Many people I know experienced this hope in that first year, too.

On a personal level, things were more or less good for me, too. We weren’t too worried about money and had actually a great quality of life during the lockdowns. We had scored a big, relatively inexpensive apartment near Griffith Park. We walked, hiked, and ran in the hills almost every day, had plenty of time to think and write, befriended (and illegally fed) a sad and gimpy pack of coyotes that emerged from the hills when people and cars disappeared for a while. But the best thing of all was that Evgenia found out she was pregnant. So I was going to be a father soon. I was happy and had faith in the future, even if the future was uncertain.

All this was overshadowed, though, by the growth and the toxicity of the online world and my increasing cynicism about my profession — journalism. It had to do with Substack.

When I first started writing on Substack a few months before the pandemic hit, it seemed like a great deal. I was planning on writing another recovered history book — this one focusing on how the United States weaponized nationalism and ethnic identity in its war against the USSR. I pictured it being half history and half memoir/biographical, as my own life as a Jewish Soviet was bound up with this program. It was nice to be liberated from traditional publishing. I didn’t need to waste my time pitching and convincing editors to run stories or have to water down my style. And anyway, there weren’t that many opportunities to publish anymore. Journalism had pretty much collapsed. Publications were going bankrupt all the time, and freelancing had become a joke, paying only a few hundred bucks. So I worked on researching this future book, publishing longish historical investigations when I had something to say. People signed up, and it seemed great. Meanwhile, I kept pushing the tv project — still hoping that Surveillance Valley would make it to the big screen.

But as we all got deeper into COVID and I realized that the TV show was truly tanking and that there was no more money coming down the pipeline, I started to get frantic. I wanted to squeeze more money out of my Substack. I needed the cash. So I started moving away from doing historical investigative journalism into more quick influencer-type stuff to stay relevant and be part of the news cycle — with an eye for increasing my paid subscriber base. Right away I noticed a couple of things. The first and most obvious one was what made money and what didn’t. The quick, very topical reaction stuff — writing about what everyone else was writing about, being part of the news cycle — that’s what brought in the eyeballs and the subs. The more scandalous, the more tied to rumors and big personalities, the closer it was to what was on cable news, to what all the other political influencers were talking about it, the more money it made. The longer investigative work that I was doing — the stuff that took time to research and write, well, that could do okay. But it stood outside of the news cycle and so it wasn’t really interesting to people. And so in the end it would barely register. Doing longer historical investigative work was why I had started my Substack in the first place. But I quickly learned that it didn’t really pay and was basically unsustainable. The effort-to-subscription ratio didn’t pan out. It was operating at what was basically a loss. And so I gradually abandoned the longer stuff. Because what readers really wanted — what they craved — was what fed into the news cycle and fed their daily political dopamine habits. People wanted their biases confirmed to them over and over and over again, to have someone hate on the people they hate, to rail against the things they don’t like, and they wanted it in quick bites, and they wanted it at exactly the same time that other political influencers were talking about it. That was what made the money on this direct-to-consumer platform.

Part of these realizations, the instrument that rubbed this obvious truth in my face every day, was Substack’s NASDAQ graph. If you’ve ever run a paid Substack, you know what I’m talking about.

Every time I’d log in to write a post or even just to reply to a comment someone had left, I’d be confronted with a landing page that looks like something a day trader would see: newsletter growth, estimated annual revenue, stats on paid and unpaid subscribers, little boxes containing how much my stats increased or decreased over the last month — or six months or year. And then I’d see the stats broken down by every email I had sent out. So I’d see right away what made money and what didn’t. I found it a little irksome. It was like opening up a portfolio and seeing how much money my trades made. Except in this case, I wasn’t buying and selling stocks or bonds or crypto, I was putting my own ideas — little bits of myself — for sale and seeing how much they fetched. In real time, too.

Initially, I didn’t think much of it. It made sense that there’d be this graph. I was running a business, right? Substack trying to be helpful. It was trying to empower me with information. I didn’t consider that this chart would affect me and just keep writing how I always wrote: about the things that interested me. But over time, I began to feel the cumulative effect of seeing this NASDAQ chart.

I was constantly being confronted with what made money and what didn’t, all while worrying about my earnings and eyeing the news cycle and considering what to write and what topics to cover. It all conspired to push the money question into my thinking. The impact was subtle, to be sure. But it was there nonetheless, and I felt it get stronger over time. And by the end of the first year of COVID, I started to feel it very distinctly. It was the power of the market: an invisible force that was trying to dictate to me what I should write about and how I should write about it. It was a voice whispering in my ear, telling me what should interest me, and by extension, what should interest my readers.

The Substack NASDAQ graph trending down signifies personal failure. “You are a loser in the marketplace.”

Money was always involved in the journalism I did. But it was never so direct. There was always a level of abstraction to it. Back when I still worked for magazines and newspapers, I’d still get the same salary regardless of how many new subs my articles brought in. I’d get the same fee for writing a story, regardless of how many hits it got. So this was different. It was more direct. Indeed, you couldn’t get any more direct. And it started fucking with my head. It started getting me down. Not only did I feel the push of the market on my own thinking and writing, but it began to color how I saw my colleagues and friends in the journalism and media world.

Bit by bit, this new direct-to-consumer journalism model pushed a dark neoliberal view of the world on me. I began to feel that everyone was in it only for personal enrichment — that nothing else mattered to them. I began to doubt the motives of friends and colleagues, people who I knew for a fact weren’t cynical and were in it for the right reasons. But it didn’t matter. Sucked into this weird marketplace of ideas, I couldn’t shake the thought. Like in Inception, the idea had been placed in my mind. I began to see everyone as cynical and self-serving. Politics and political journalism is about morality. And I saw everyone as using this morality as a tool to extract cash from their readers. I began to see examples of them playing to the market everywhere I looked — from the guests they had on, to the angle from which they covered a story, to the sexy selfies they posted with their hard-hitting journalism from the frontlines, the way they swerved from topic to topic to stay with the market or flip their positions because the money pull was much greater on the other side.

People talk about the “marketplace of ideas” — and this is exactly what I felt I was inhabiting: a market where ideas and morality were for sale. And like any big global market, it was full of bullshit and hype and big powerful actors working behind the scenes manipulating it for their own purposes. And of course there were the big platforms — owned by our ruling class — controlling the algorithms and profiting off of it all.

What depressed me even more and made me even more cynical about the situation was the realization that much of American politics these days revolved around various media influencers. They are at the center of our politics. It’s not politicians or political leaders, it’s influencers — they’re at the helm of political culture. And all these influencers, myself included, based their livelihoods on the logic of the market.

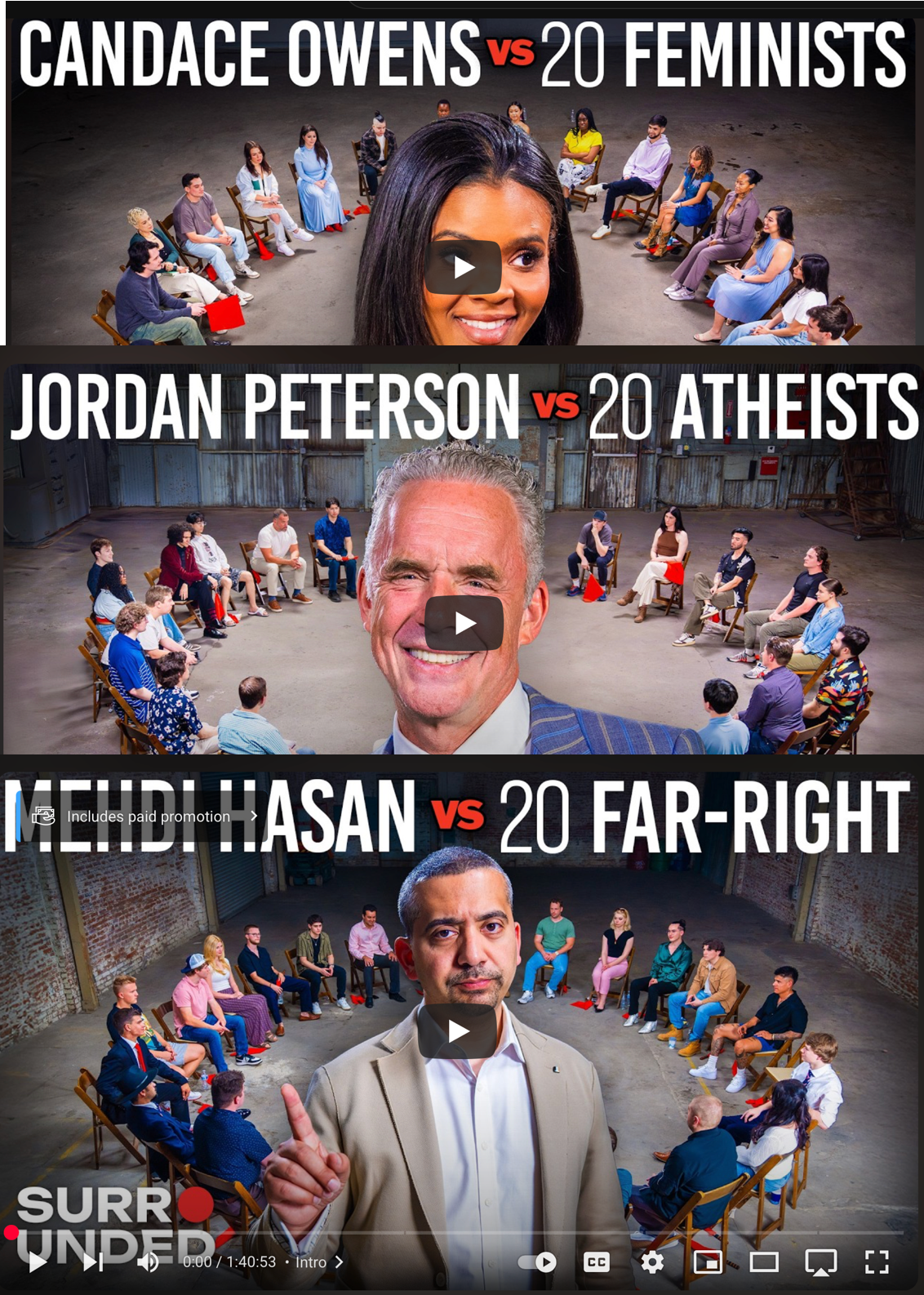

What’s interesting is that a distinct type of genre emerged from this technology and the market forces that shaped it: the celebrity interview. Think about it. All the big new political media personalities are all about the interview now. That’s the innovation that it foisted on us: famous influencers interviewing other famous people. That’s the main political content we all watch these days. Evgenia has been talking about this for a while now: the celebrity interview as the dominant form of media that the internet has produced. Not films or shows or even any new type of art. Just interviews with famous people. I think it is significant because it ties into the market logic of these direct-to-consumer media platforms: famous people interviewing famous people is what brings in the eyeballs. It’s low effort, high reward. It’s synergistic. Like two brands doing a collab, both bringing in their fans…doubling the audience. It fits with our atomized age where no one hangs out and talks anymore. People need their digital parasocial relationships. The podcast is the ersatz circle of friends they don’t have. So people love the interview format…can’t get enough of it. And they want more. But interviewing famous people is not enough to drive the clicks anymore. Even panel discussions where famous people scream at each other is not enough. Now you need to put famous people in a circular brawl — you need media gang bangs!

A combined 30 million views on these clips. Think of the ad revenue!

All this feels a little bit ridiculous. I look around and I think, Why the hell did I even get into this profession? I mean, I never wanted to be a journalist. It wasn’t something I dreamed about in high school or college. I didn’t have some civic high school debate team dream of helping American democracy run efficiently. It happened purely by accident. I moved back to Russia after graduating from college and needed a job to support my very frugal lifestyle. And a distant cousin knew someone who knew an editor who was looking for a stringer to file periodic stories from Russia for an American news wire. Right away, after the first few stories I filed, it was clear that I had a talent for it. I could naturally sniff out a story, people talked to me, I could bluff my way into places I shouldn’t be, and I could explain myself in a clear and mildly entertaining way. So I worked as a stringer for a while and then moved over to The eXile in Moscow and got into the more aggressive gonzo-satire side of the business, and I liked it. My previous and only other “professional” job was working at a factory in Berkeley as a technical writer, writing elaborate instruction manuals for assembly line workers who were putting together super high-end concert speakers. So this was an upgrade — a much more interesting way to scrape a living together. But I didn’t take journalism very seriously and never had much respect for journalists — seeing them as usually little more than propagandists and suckups to power. I never thought I’d be a “serious” journalist.

It was only when I moved from Moscow back to California right after the 2008 Wall Street crash and began covering the aftermath of that collapse that did I really start to feel the power of journalism and started taking it seriously. I got a real taste of it when I helped expose the hidden role that Charles Koch, the head of what was then the richest and most politically powerful family in the United States, played in bankrolling the Tea Party Movement — a pro-austerity astroturf campaign aimed at stopping the Obama administration from providing financial relief to homeowners who got screwed by Wall Street when the housing bubble burst. Back then, America’s entire political class had believed the Tea Party was a natural expression of populist anger — and we stumbled, almost by accident, on a whole network of oligarch-funded groups that were orchestrating, coordinating, and bankrolling a movement aimed at stopping government program that would help regular people facing foreclosure at a when all the Wall Street banks were getting stuffed with government bailouts. It’s all half-remembered now, and seems like old news. But it was one of the largest stories and political scandals of that era and an important chapter in recently American history — one of the last nails in the coffin of the Democratic Party. Of course, Obama, being the Wall Street sellout that he was, caved to the demands of the Tea Party, and the program to help the small guys fucked by the big banks didn’t go through while the bailouts to Wall Street continued to flow. Those with connections got theirs while everyone else got fucked — with help from Obama. We dragged the secretive political network backed by the Koch family out of the shadows and put them on the map and tried to educate people here about how power really worked in America, and how much of a stranglehold the oligarchy has over the culture here. But it didn’t really matter. The American people have short memories and channelled all their resentment into electing Trump, as much of a pro-oligarchy president as the previous guy.

But at the time the Tea Party story was pivotal for me. It ultimately turned me “serious” and sent me into political and investigative journalism. It drew my interest to the complex economic systems that surround us to the point that we don’t even recognize they exist. Who controls them? Why? It’s why I was drawn to reporting on California’s water politics and the secretive oligarchic families that controlled the state’s water supply. And this interest also led me to think and write about the origins of the internet — leading me to recover a lost strand in the history of this technology, showing how the internet was developed by the US military as a tool of political and social control. That research became Surveillance Valley.

Until then, I still had a somewhat naive idea about how America worked. I didn’t think that everything around me would be in control of such a tiny number of people, not such complex globe-spanning systems could have such simple and nefarious origin stories. The more I learned, the more I realized that underlying it all there was a vast centralization of power in America — a centralization that seemed very similar to the kind of control I had seen in Russia. My own journalism helped me educate myself and strip of any illusions regarding American Exceptionalism, an idea that had been drummed into my Soviet immigrant mind. It also revealed something about myself to me: that I’m moralistic, that I chafe at the unfair exercise of power, that I don’t like bullies, and in fact that like bullying the bullies. I realized that this was a big part of my personality and journalism allowed me to express it…it allowed me to fuck with power way beyond my means. Even an immigrant nobody like me could wield power against our shitty ruling elite — someone with no money, zero connections to power, and no pedigree to speak of. I was educated in second-rate American public schools and most of my childhood friends never went to college and here the most powerful family in America was sending its media assassins to bury me in dirt.

That’s what got me into journalism. It wasn’t money. There was none. It was morality and a sense of personal and collective empowerment. Obviously I wanted to make enough money to live but it was never the motivating factor.

I’m not naive. I know lot of journalism has always been about cynically chasing attention and riling up conflict for clout and prestige. People have always cynically peddled morality for power and money. But there have always been exceptions — weirdos and freaks like me who weren’t cynical about what they were doing…people who were into it because they really cared. Thinking about this during my first few years of Substack bummbed me out even more. Because I began to see these exceptions — the idealistic weirdos and the freaks — were also falling under the control of these unseen market forces. No one could escape. It was systemic. The platforms allowed the direct commodification of alt-journalism, a part of the profession that had never really been commodified before. And it was too hard to resist. And why resist? Who could say no to money, especially if you were already doing pretty much what you were doing before?

I don’t know…maybe it seems simple to think this way. But seeing money and morality mix this way got me down. It bothered me. My belief in the power of journalism to make a difference was already at a very low point by the time COVID hit and I went on Substack. And being part of the influencer economy from the inside made it collapse even further. So much of it now was just about maximizing clout and gaming the algorithm for reach…

About a decade ago, people were really excited about the rise of the direct funding platforms — Patreon, Substack, YouTube, and now a bunch of small rival platforms that basically do the same thing.

It was seen by many as the realization of the internet’s democratic promise. Journalists, essayists, cartoonists, filmmakers, and basically anyone could now completely avoid editors, publishers, and various authoritarian media gatekeepers. The people were now free. We were now free to directly interface with others…rising on the strength of our talents and abilities. It was purely meritocratic. And there was truth to it. But alongside it was another truth: There’s no editor telling us what to do, but there was something equally powerful: the market. It pushes and nudges, it regiments…It’s all very subtle, too. The control is basically invisible. And lack of success can be explained as your own personal failure, rather than the censorious nature of what the market wants.

The problem goes beyond just journalism. The market affects everything it touches. There are all sorts of examples of influencers being driven to do horrible and destructive things to keep the god of the market satiated — destroying their own bodies, abusing kids… I’m thinking now of that Mormon mom who kept her kids in a gulag to make sure her YouTube channel kept going or the woman who adopted a child from China for clicks and then dumped him because he was just too much work. Mr. Beast is the face of this relentless market force…what began as funny stunts have driven the man, in search of greater and greater shock value and clicks, to essentially recreate Squid Game. The algorithm and the market push you in a certain direction. And it’s relentless.

Looking back on my own Substack journey, I guess I tried to ward off the evil market forces by doing the opposite of what it pushed me to do. In a classic self-destructive defensive mechanism, I began to get even more fringe in my work…to write about stuff that only a tiny group of people would find interesting. I stated to plow the depths of my family tree…writing about my grandparents and their lives. Basically, I rebelled by making sure I didn’t make any money. But that didn’t solve the problem, and in the end, only made me even more depressed. Why the hell am I doing this if I can’t make enough to live and to support my family? If the media business is so shitty, why not just get out? It sent me on a spiral, and there were a few moments when I almost exited the media world for good. I thought about going to med school and at one point was seriously considering opening up a sourdough bakery. It’s funny, too. My book Surveillance Valley was about how the internet began as a Pentagon pacification technology. And here the internet had to work to pacify me, too…pacifying me by poisoning my mind. I was a journalist who liked to fight power, and yet here I was being disarmed — made cynical and nihilistic and bitter. So in the end, this neoliberalization of the media self was doing its job. I was being taken out of commission.

Ultimately, I stayed. The way I saw it, there is a war being waged for the hearts and minds of humanity, and I couldn’t let the evil fuckers win. I couldn’t cede the field of battle to them. But still, I continued to have my doubts. Why should I stay in the fight? Who are these imaginary people that I’m fighting for? Who are these masses that are just waiting to be saved? Am I some kind of insane media Stakhanovite, working overtime, blasting through production goals, working for the collective good…but the collective doesn’t care about me nor does it even care about the collective. What the hell was I doing?

And then I’d go into this Debordian Hall of Mirrors debate with myself. We live in this society of the spectacle…and the people want their spectacle…they demand it. The people want their media algorithmic slop. They want their titillating sex scandal Epstein drip. They want their outrage bait…their C-level celeb roundtables screaming at each other. They want their QANON and BLUEANON and Call Me Daddy interview brainrot. Sure, the market is evil. But the market can’t function without a consumer base — and “the people” love their media garbage. This is what they want…this is the content they crave. So who am I to get between the people and their entertainment? Who am I to fight it? Let them have their slop. And then I would get philosophical about it. We’ve been conditioned to believe that “information is power” — it’s taken as a basic truth in our information age. But is it true? Because as far as I see it, it’s always been an illusion. Information isn’t power. It never was. Unless you have power, information is just information. And you don’t need much information to build power, you need an idea and belief and you need people. So in our consumerist-spectacle society, information without power becomes just that: a spectacle. And then I think further: What does it mean that all politics is now mediated through the influencer — that the influencer has become our politics and that the influencer, no matter how well meaning, has melded with the spectacle and promotes the spectacle as liberation? Can you even fight the spectacle from within the spectacle by giving a better spectacle? Seems like the answer is, no. Entering the spectacle, we become it. But if the spectacle itself is the problem, then we have to end the spectacle. Right? That should that be our goal? Ending this circular ersatz media existence? And so I come back to square one — maybe I should go to med school after all.

I was just talking about this with Evgenia, and she now leans towards the need for a dictatorship in the early Soviet style of Proletkult run by people like Anatoly Lunacharsky. The problem, to her, is that the people don’t know what they want. What they need is guidance. They need enlightened curation. They don’t need the marketplace of ideas, where their basic instincts are juiced by a malicious media oligarchy, an oligarchy which is itself trapped by these same basic instincts. And I can’t say I disagree with her. The spectacle can’t be the thing that runs the world.

What we really need today — what we need right now — is some enterprising young Luddite-terrorists to destroy the internet. The internet was designed to be decentralized — designed so it could survive a nuclear decapitation strike…designed to be like a fungus or a cancer. But centralizing capitalist society is its own enemy in this regard. So much of the internet is now concentrated in a small number of data centers around the world that its infamous decentralized function has been effectively negated. It is now feasible to take the internet out — or to take out a substantial portion of it to cripple it for a few years. And maybe those years will be enough to let the human race recover from the burden of this spectacle and give us a chance to return to the real.

—Yasha Levine

Want to know more?

Thanks for sticking around. I've always appreciated long-form intellectual articles (that fall short of reading a whole book) that let me think.

It looks like we are really in an experiment of pure market takeover/integration into every facet of life, where it's essentially impossible to leave. Maybe the purpose of this is to provide future generations with a definitive statement of what capitalism is, the same way Israel has written its definitive statement on Zionism, and in that recognition they can choose to do something different.

But in so many industries we now have direct individual subordination to market tendencies. The irony is instead of a stifling publisher, record label, practice, or company acting as a barrier, we face these coercive forces in the raw. Just thinking about being a therapist, ethically you don't want to be financially reliant on your clients. But if you work independently, you are inherently reliant on clients, and this creates a conflict of interest. Everywhere now there are all these conflicts of interest and "incentives" that warp or pollute the function of most aspects of society.

If someone blew up the internet, in the West we'd have a really hard time as the industrial backbone of production is largely gone. Some friends have been proposing how to escape AI influence in the music industry, and one idea is to do everything analog, with tape, and make vinyl records, physical artifacts that have never touched computers would have more inherent value. But we don't actually have the capacity to be making tape, or records, or even analog recording consoles, nor does distributed capital exist to afford building these costly studios. I think the same is happening with book publishing, and happened years ago with film.

I do appreciate what you do, and I do feel there is intentioned signal that makes it through the noise. Having a systems-level detective working for the collective mind has to be important, and even if we are (temporarily?) captured by the system, our minds don't have to be. Unless the extreme-long shot possibility of Evgenia's dictatorship of the proletariate happens, we may have to wait until human tendency and culture finally overindulges in these impulses to such an extreme and absurd extend that we all get sick and decide to move on and wake up a little.

Here's a weird thing about the internet: if you quit writing, I'd feel like I lost a friend. Reading your essays is often a highlight of my day. It's bizarre and irrational, but deep writing that resonates with your own thoughts makes you feel like you found a soul mate. What sucks for the author is that they rarely get to know it, and the little box I'm writing this comment in is entirely inadequate for explaining the depth of this one-sided emotional connection. I'd like to think that somehow, through the fabric of the universe, you'd occasionally feel it, but of course we both know it's bullshit. Nevertheless, this is very real and meaningful to me, and I truly appreciate you.