A research note on the Holodomor and forgotten Roma victims

When I wrote last week that I won’t do anything on the Ukrainian famine again anytime soon, well, I guess I lied!

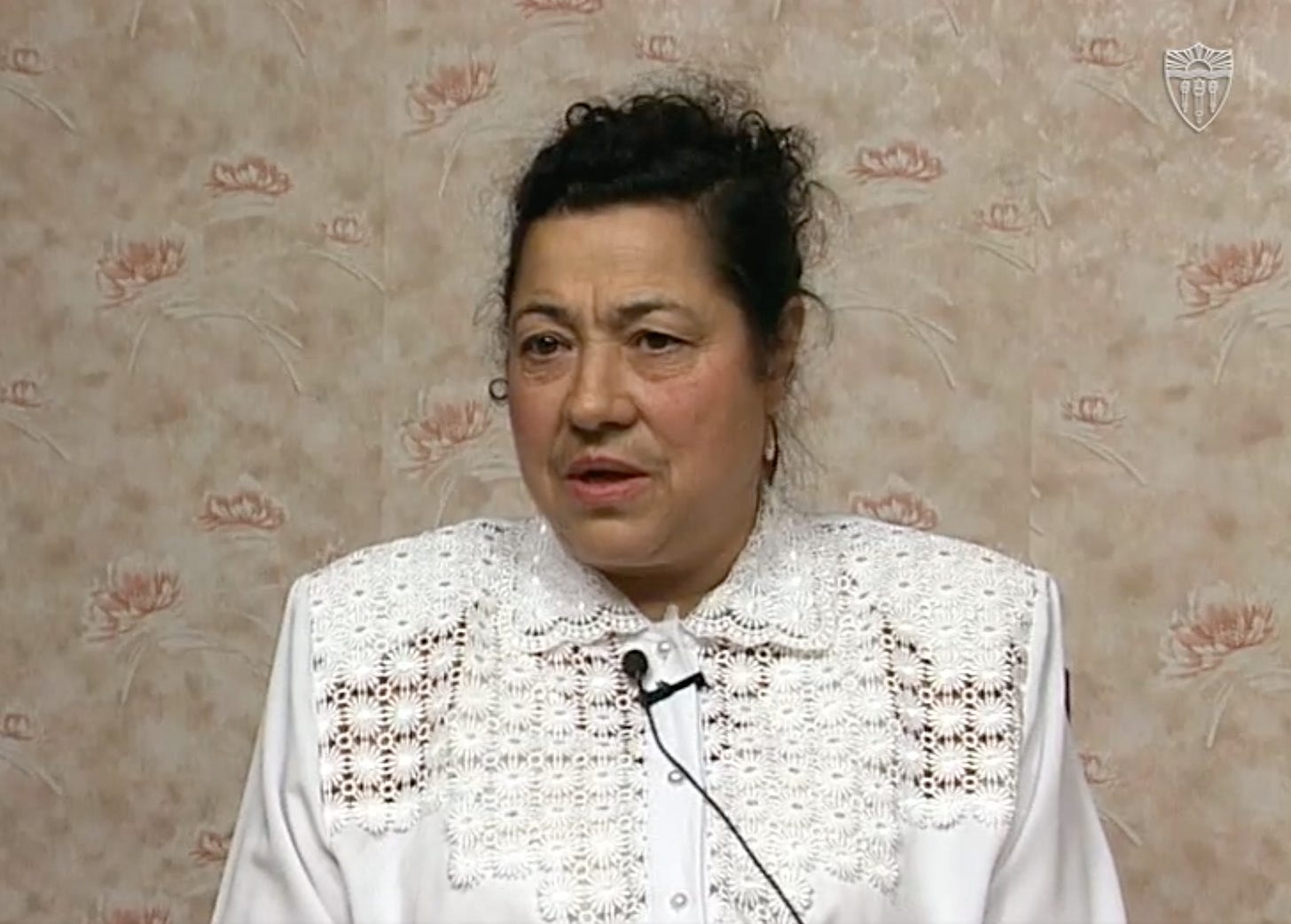

Anna Ryzhaia

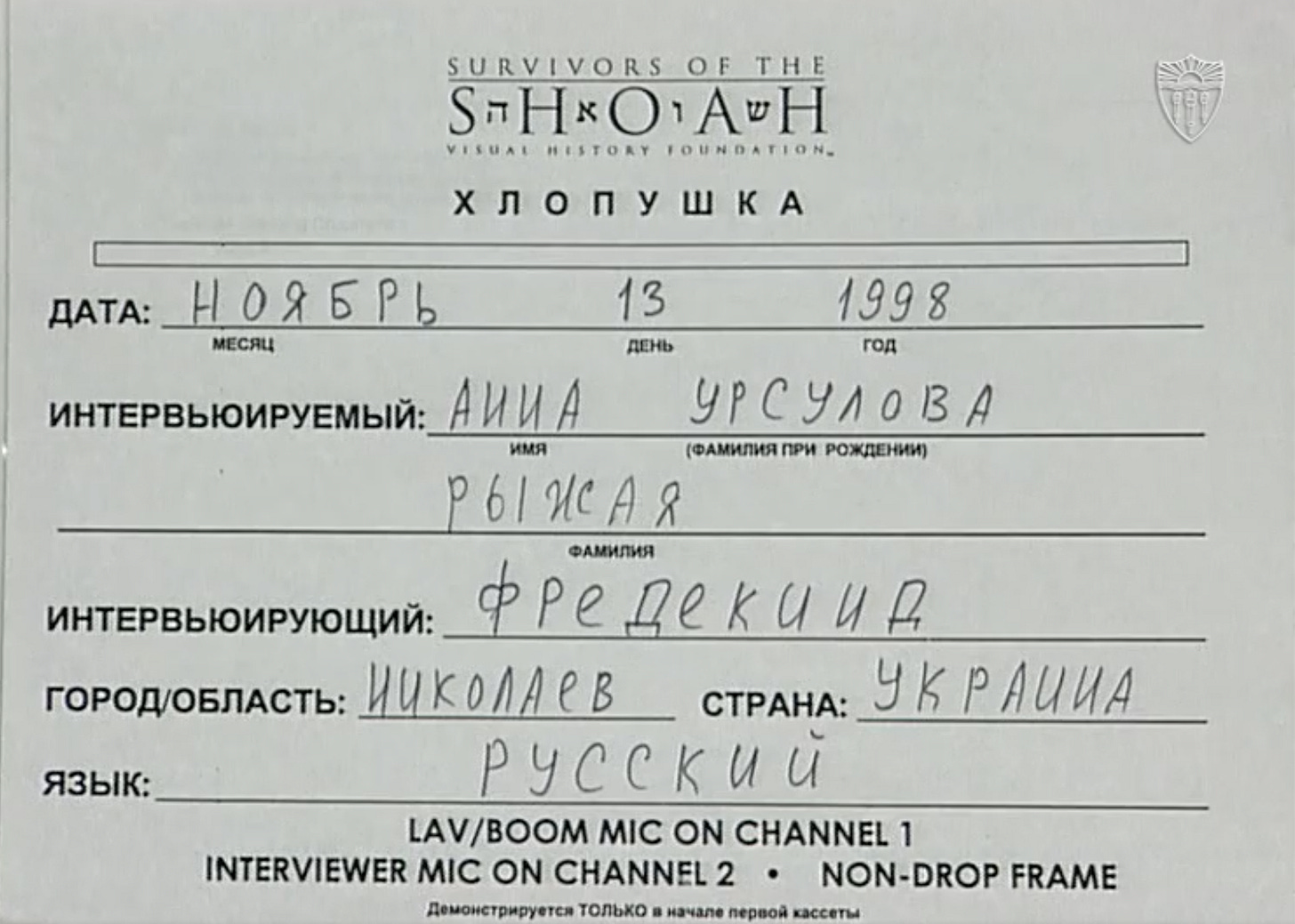

I was organizing some notes from my research into the famine’s forgotten victims and came across an interview that I almost forgot about. It’s with Anna Ryzhaia — a Roma woman born in Ukraine, Nikolaev Oblast, in 1937.

The interview was done in 1998 as part of an oral history project set up by Steven Spielberg after his film Schindler’s List. It’s now hosted at the University of Southern California, his old school. The oral history collection is primarily focused on testimonies of people who lived through World War II and survived or witnessed some aspect of the Holocaust. Because there is some overlap between people who lived through the war and those who lived through the 1930s, or at least knew people who lived through the 1930s, it also has interviews with people that tangentially touch on the Soviet famine.

The interview with Anna Ryzhaia was one of those. It gives a glimpse into the Holodomor/genocide question from the perspective of another ethnic minority that lived in Ukrainian SSR during the famine, and which has also been excluded from the Holodomor narrative: the Roma.

I wrote before about how Jews got left out of the Holodomor genocide story because their inclusion as victims of this tragedy wouldn’t fit the clean line about the famine being a (Judeo) Bolshevik plot designed to wipe out ethnic Ukrainians. There were about 1.5 million Jews in Soviet Ukraine at the time. They too suffered from the famine. And their absence from that history says a lot about the political spin given to the Ukrainian famine today.

Listening to Anna describe what she knew about her family’s ordeal during the famine shows that the Roma — who mostly lived an itinerant lifestyle in Ukraine and who like a lot of Jews worked as shoemakers, blacksmiths, traders, and various artisans — also suffered, as one would expect.

As she explained to the interviewer:

“My father told us that when there was the famine in 1932 and Tatyana [her sister] was small, they were somewhere in Crimea. Because in Nikolaev there was serious famine. In Crimea, according to stories my father told, it was probably better because they all survived. And when they all came back, this is why I remember this very well, my mother’s or father’s cousin — her name was Lena — she said that she was horribly bloated to the point that she had worms on her. That’s how bad the famine was. …When (my mother?) breastfed Tatyana — this was of course all told to me later — she had no milk and couldn’t really feed her baby.

She does not dwell on the famine too much. But the small bit of info she does recount just confirms what I wrote about earlier: the current Holodomor narrative that tightly focuses on ethnic Ukrainians leaves out all other minorities living on Ukrainian land — including Jews and the Roma.

The interview with Anna is in Russian and doesn’t have English subtitles — so most if you probably won’t be able to watch it. But it’s got great stuff all the way through. For instance one interesting thing Anna described was how intermixed Ukraine was — with multiple ethnic groups living side by side: Ukrainians next to Jews next to Roma next to…German colonists who came to Ukraine in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. As she explained, her family — which was mostly involved in shoemaking — lived among German settlements in and did so much business with the Germans that her parents spoke German better than spoke Russian — which is surprising because her Russian is very good. She explained that her parents’ knowledge of German was probably what saved her and her family when the Germans swarmed and occupied Ukraine. Other Roma families — and Jews, too — were brutally murdered on the spot.

Anyway, lots of interesting forgotten stories about the famine. But none of it matters really. They don’t neatly fit the politicized frame.

—Yasha Levine

Want to know more?

Thanks, Yasha, for sharing forgotten or deliberately neglected pieces of the Holodomor tragedy of death and suffering.

Perhaps the next and certainly final research note should be about how suffering and dead Russians got left out of the Holodomor genocide story. Cheers, Igor (Jew from Odessa)