The Disappearance of Barbarians

How the Soviet Union psyoped itself out of existence.

On December 25th, thirty-five years passed since the Soviet Union officially died. I’m very much a contemporary to this event and to post-Soviet Russia. I was the first generation who never experienced life in Soviet Russia but grew up in capitalist Russia with Snickers commercials, Disney cartoons, and Arnold Schwarzenegger movies. These American artifacts are my earliest memories, which one would think is quite bizarre considering that I was born in Moscow, that my native tongue is Russian, and there were more than enough native cartoons and movies to grow up on. But the thing is, at the time, the Soviet Union was no more, and all Soviet media production — with its Soviet morality — was under suspicion. People were hungry for American cultural output. Throughout my childhood and youth in Moscow, this foreign product was considered magical and superior and even more truthful. I watched Dallas and Santa Barbara soap operas on TV with my mom as a kid and thought, “Wow, this is America!”

Now, though, having become an American and living through the decline of the American Empire in its very centre — New York — I do wonder if this is how it felt to be in Moscow during late Perestroika. A big part of America’s intelligentsia seems to be more and more disillusioned with the American myth, in American Exceptionalism. Meanwhile, the other part of America is doubling down on it and joining quasi-fascist “old guard” forces that are promising to keep the myth strong as ever…

As I’ve been writing and saying for a while, this American unraveling feels vaguely familiar. I was born during the unraveling of another mythic empire and grew up in its postmortem, a world that was like Fellini’s (and Petronius’s) Satyricon — a proto-Christian world where there was no faith and where basic instincts and base pursuits reigned in society, or what was left of it. Except Russia was post-Christian. It rejected communism, a faith that was rooted in Christianity.

Despite numerous historical books and journalistic reports, it is still quite dumbfounding to me and to many other people how exactly it happened that the USSR came apart. A book I recently found while on a family visit to San Francisco has an interesting theory of it. And it’s this: The Soviet elite actually believed American propaganda about the Soviet Union. And this elite themselves demonized the Soviet Union into extinction. The Voice of America and Radio Free Liberty were, in the end, very successful in carrying out their mission: to destabilize and topple the Soviet Union from within, despite all the censorship and Iron Curtain protections the Soviet Union put up in defense. In fact, this attempt to wall itself off from the West contributed to its demise, since no one could really experience the West as it was and relied on an idealized picture of the West they had in their heads — a picture drawn, in large part by American propaganda and Hollywood.

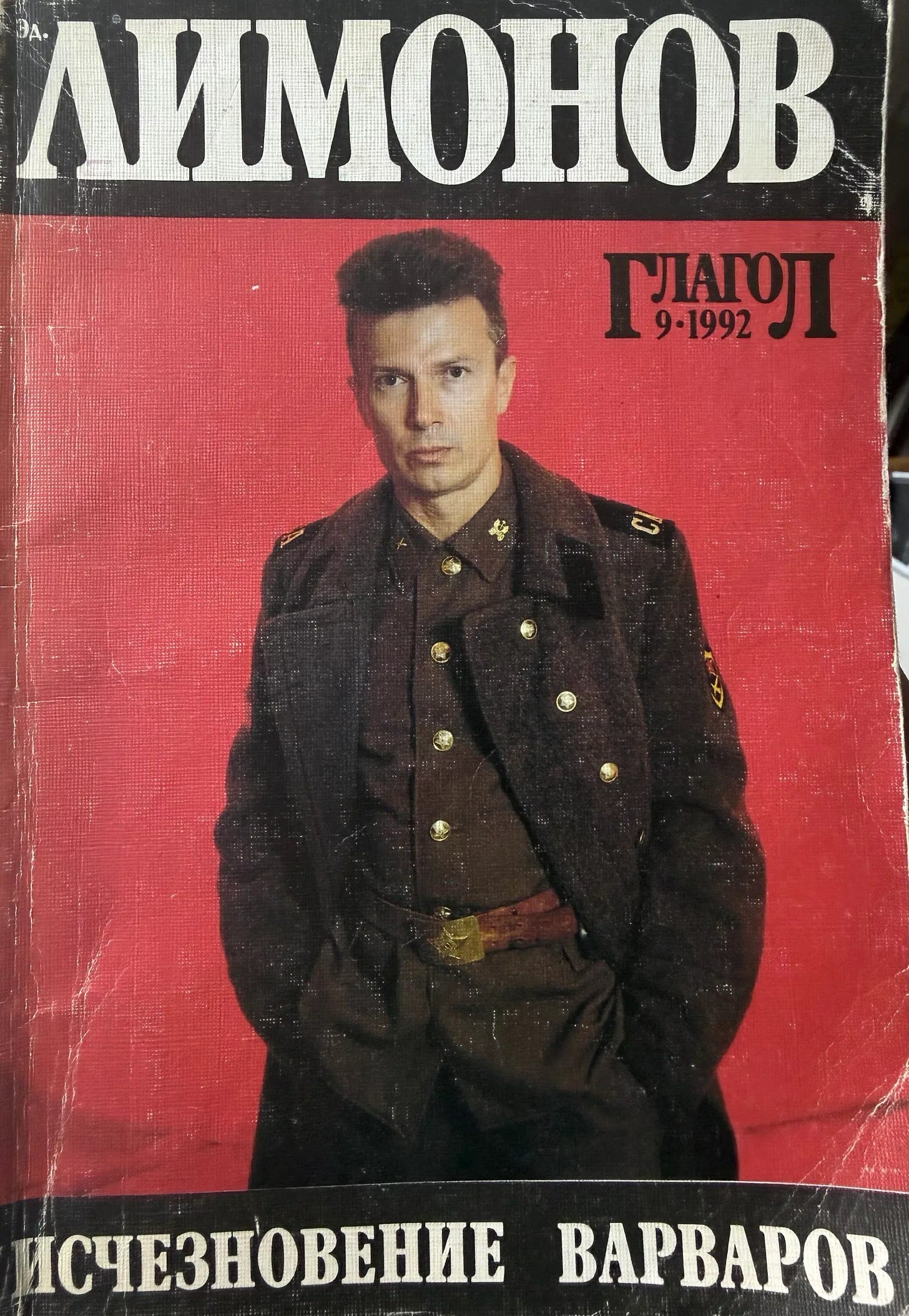

I found this book mysteriously on Christmas Eve. I was visiting family in San Francisco. And after the electricity turned back on in Little Russia out in the Richmond District, I walked into a local Russian bookstore with my daughter to get her something. But instead of getting a kid’s book, an old Eduard Limonov book caught my attention. It was an old collection of articles he wrote in the 80s and 90s — released under the title of The Disappearance of Barbarians. Limonov published these articles in various newspapers that had proliferated during Perestroika, when there was a brief moment of a completely free press in Russia. For many back then, it seemed like the end of the totalitarian stifling era and the beginning of something exciting and new. But, well, Limonov knew better…

In the late 80s, Limonov, along with many other Soviet exiles to the West, became quite active in the Soviet media scene. But he stood out. He was pretty much the only voice of reason among the pro-Western market Bolsheviks and intelligentsia, which was obsessed with turning Russia into a “capitalist and democratic paradise”. Limonov had lived in the West for over fifteen years, and he was disillusioned with it. He wasn’t ignorantly hateful, though. He was critical the way a person can be critical after having experienced it fully — as an immigrant on welfare in New York City, as a laborer upstate, as a published writer, and then as a journalist in Paris. He wasn’t a Soviet privileged tourist or celebrated dissident or a coddled official immigrant — like a scientist or mathematician or professor with a good cushy job at a prestigious Western university. He really had to live in Western society on its own terms without institutional support or a safety net. He saw the highs and the lows of Europe and America. He really “went to the West”.

What made his perspective valuable was that he was anti-Soviet while he lived in the USSR and was part of the Moscow underground art world. As he explained in one of his columns, he listened to Radio Liberty (founded and run by the CIA) like everyone else in his circle and believed everything that was said there. Back then, also like everyone else in his circle, he only noticed crude Soviet propaganda and did not understand that there was also such a thing as Western propaganda. For instance, Limonov retells how in 1968 he listened to Radio Liberty talking about Soviet tanks entering Prague and crushing the uprising there. He was himself critical of what the USSR was doing in Czechoslovakia, but he only later realized how one-sided these Western news programs were. They didn’t at all talk about Western crimes — like, for instance, the My Lai massacre in Vietnam, a much more horrific violent event that was happening pretty much at the same time.

To Limonov, this was just an example of something that was very common in his Soviet baby boomer generation — the generation that dismantled the USSR. His generation was comically ignorant and naive about the West, which it mostly knew through CIA-created radio broadcasts like Radio Liberty, occasional Hollywood movies that made it to the Soviet Union, and limited trips abroad by its bureaucrats and scientists on which they only saw the best and most elite parts of Western societies: top academia, government, and corporate sectors. And any criticism of the West, which came from their own Soviet government, was dismissed as propaganda. The racism, the poverty, the reactionary politics, the massive body counts from all its foreign wars — all this was seen by Soviet people as a lie or extreme embellishment, even when the criticism of America was really on-point. In short, they idealized the West and demonized everything about their own society. They loved the West and hated their home with a passion and purity that they reserved for no one else. People like to talk of disinformation these days. Well, Limonov’s generation was raised on a lot of disinformation about the West. This led them to, eventually, dismantle their own society from within, Limonov argues. In short, the Soviet Union psyoped itself out of existence.

Limonov would’ve probably remained one of these disinformed Soviet boomers, if not for his forced emigration to the West in the 1970s. He was kicked out of a quasi-socialist oppressive-but-secure world into the free capitalist world — a world everyone in the USSR was only dreaming and reading books about. In the West, he gained real experience. He knew more about the West than the reformers who dismantled the USSR — partially out of a genuine desire to restructure it and to make it better, more democratic, and more Western. They, like all Soviet people, only understood the West from afar. They only knew the myth, and so they pursued the myth.

One big insight that a mature Limonov tried to share with a still-naive Soviet people in the late 80s is that a lot of what he believed to be “Soviet propaganda” about Western capitalism turned out to be not propaganda at all. Violent exploitation of European colonialism, a rigid class system, the bourgeoisie holding all the power, regardless of political parties — all that turned out to be true. In a way, through emigration, Limonov discovered the “victims of capitalism” that he had no idea about while living in the USSR.

He wrote:

“Soviet intelligentsia keeps digging more and more to find and expose crimes of their country, and by doing it, they are destroying the foundation of the Soviet/Russian state. Raised on outdated political and economic theories, they know the West only through books, postcards, and tourist trips. Nihilistic intelligentsia is ignorant and often dumb. Intelligentsia accuses the Soviet Union of crimes that are common to all states and all economic systems. Their ignorance leads them to equate their nihilism with democracy.”

In one of these articles from 1990, Limonov concedes that Gorbachev was honest and well-meaning, even if soft. Gorbachev wanted to de-Stalinize the USSR — to bring “socialism with a human face”. But he was also a provincial country bumpkin, “the first generation in his family to get a higher education, a person who joined the Communist Party aquarium early in life”. Decades before Vladislav Zubok’s, influential book Collapse, Limonov described Gorbachev in very much the same way: as very naive and ignorant about how Western democracies worked and about how power worked in a complex and fragile society like the USSR. I’d add that it’s no wonder Gorbachev ended up defeated, dethroned, and in a Pizza Hut commercial.

As Limonov explains, much of the Soviet intelligentsia — along with a part of the Communist Party aristocracy like Gorbachev — was on a self-flagellation binge. It was masochistic and inane, since Khrushchev had already denounced Stalin in 1956, three years after the leader’s death. So this new wave of perestroika’s public humiliation ritual was excessive and dangerous, as Limonov writes. No left intellectuals — let alone anyone in power — in France or America would go that far denouncing their own country into extinction and suicide in the name of reform. If the USSR is so uniquely evil, why would you even want to keep it reformed?

What I find fascinating about Limonov’s essays is that they were written right as history was being made in real time and widely published. He was right about most things. And yet he had no real effect on politics — at least not right away. Looking at it now, it’s clear how darkly prophetic he was about the outcome of this dismantling. Back in the early 90s, most Russian “democrats” called him fascist for doubting the utter evil of the USSR.

In 1984, Limonov published a short sci-fi story in the French magazine Zolou. This essay collection takes its title from it — “The Disappearance of the Barbarians”. Despite the story being rather crude, it’s very accurate politically. It’s a story about a world where the Soviet Union one day just disappeared and only white gypsum remained on its whole huge surface. This led Western countries to freak out — losing an enemy wasn’t in their interest. They needed it to function to have big military budgets, to scare their population into submission, etc. So they tried to covertly convince China to become their official enemy, but their leader declined and said they’d gladly give in to Americans (but secretly the Chinese plotted to just assimilate the Americans like they did with the Mongols). So the West felt hopeless. It needed the Soviet Union or Russia or whatever you want to call it. It needed “the other” to maintain its own power structure and lamented its lack.

And isn’t it exactly what ended up happening? After the collapse of the USSR, America couldn’t really deal with not having an enemy anymore. So it invented the War on Terror, but then that wasn’t nearly enough — you needed an equal foe to prop up such a giant military machine. And so Russia began to be invented as a threat — all ramping up to a New Cold War that is no longer cold but is very hot and has tanks in Europe. It shows how prophetic Limonov was in this short story as well. Blaming the external enemy for all the world’s problems — and at the same time requiring this external enemy for internal stability — is the modus operandi of the American empire.

The New Cold War as predicted by Limonov in the late 1980s is not ideological — Russia is not socialist and doesn’t offer an alternative economic system or set of values. The Cold War now is purely geopolitical and this time all masks are down. Hungry for power and resources, the American Empire can’t really hide its motifs anymore behind the usual tired slogans— “freedom, liberty, democracy”.

Among Limonov’s predictions that came true was that nationalism is back in trend again. He wrote that since the supra-nationalist ideology of the USSR was no more, violent nationalism of former Soviet Republics would be easily ignited. He writes “Ukrainian nationalism can easily ignite and wake up Russian nationalism”. Well did it not?

He wrote:

“I visited USSR in December 1989 and the country looked scary, horrifying — crimes, nationalistic uprisings, ethnic massacres, strikes are raging across the country and economy is worse than before perestroika and their is no sign that it’ll be any better soon. When I left ussr in 1974, the country was in better state and soviet people looked happier and calmer.”

In the end, he saw that Perestroika would lead down a dark path because it is naive and simpleminded, not taking in the complexity and cynicism of the world as it exists. He explicitly cals perestroika’s “one-sided altruism” dangerous and refers to its phenomenon as “Chaadaevshina,” a term he coined using the name of the famous noblemen, traveller, and philosopher Pyotr Chaadayev who saw Russia as backwards and infinitely inferior compared to an “enlightened Europe”.

As Limonov wrote:

“Altruism is great if everyone is engaged in it and all other states and nations undergo their own perestroikas. But this is not the case — in fact it’s the opposite — western head of states stole the legacy of soviet perestroika and claim that the democratization in eastern Europe is the sign of victory for capitalism over communism.

I think because of Limonov’s poetic gift (people forget that he was first and foremost a poet), Limonov can be very astute in his political articles. He comes up with terms that I never saw any liberal Russian journalist or politician to ever use. These terms help to make sense of what actually happened in USSR.

For instance, Limonov calls old Communist Party leaders — “communist aristocracy” and he calls the upheaval of early-90s a “true bourgeois revolution”, rather than a conflict between the democratic reformers and communist conservatives or as freedom vs. totalitarianism, as westerners or Russian liberals described it.

In many ways Russia in 1991 did undergo a version of 1917 February Revolution, and the revolution did stick this time around. The irony is that it was made by former (as I call them) ambitious cruel peasants turned into Communist Party-adjacent apparatchiks, who privatized whatever chunks of the Soviet Union they could get their hands on the moment it became possible. There were no Milukovs or Nabokovs in this belated bourgeois revolution — meaning no-one out of the beneficiaries of the collapse really believed in the noble aims of the bourgeois revolution they were leading. They were just grabbing and stealing what they could. They had nothing to offer society, other than that. As Limonov writes, the main trick of this new bourgeoisie was to appeal to the crimes of the past — to things like Stalinism and to Soviet stagnation — in order to take power away and discredit communist aristocracy, like for example the “Soviet hardliners” who tried to stop the collapse in 1991 and were crushed within three days. Boris Pugo and Sergey Akhromeyev, two generals who were part of this hardliner coup, committed suicide after it failed. In their suicide notes, both mentioned that they couldn’t keep living when everything they devoted their life to was no more. While in the media they were framed as totalitarian individuals who were trying to stop the march of progress, the truth is more complicated: they were, in part, acting on idealistic impulses. They truly wanted to save the USSR.

Eventually in the late-90s came the disillusionment with this bourgeois counter revolution — the same way that the disillusionment with the Bolshevik revolution was quite apparent by late 1920s.

As Limonov wrote:

“Anticollectivisation of 1990s turned out as painful as the collectivization of the 1920s. It undid the whole psychological way of life and made it obsolete, meaningless for tens of millions of people.

In an article from 1991, Limonov was shocked by what he saw around himself in Moscow. He described it as “unnecessary masochism”. To him it was strange to watch the USSR doing penance, even as the USA was entering a phase of “militarist self-aggrandizing glory” in response. This was not the reaction of a friend. It was clear to him that no matter how much the USSR self-flagellated, America would not help Russia gain prosperity and freedom for its people, and it was idiotic and naive for Russian politicians to believe that it would.

Limonov predicted that the Russian Penance period would end badly — and it did. And now Russia is in its self-aggrandizing militarism phase. But who is there to blame?

END

understood the west from afar. They only knew the myth, and so they pursued the myth.

One big insight that a mature Limonov tried to share with a still-naive Soviet people in late 80s is that a lot of what he believed to be “Soviet propaganda” about Western capitalism turned out to be not propaganda at all. Violent exploitation of European colonialism, a rigid class system, the bourgeoisie holding all the power, regardless of political parties — all that turned out to be true. In a way, through immigration, Limonov discovered the “victims of capitalism” that he had no idea about while living in USSR.

He wrote:

“Soviet intelligentsia keeps digging more and more to find and expose crimes of their country and by doing it they are destroying the foundation of soviet/russian state. Raised on the outdated political and economic theories, they know the West only through the books, post cards, tourist trips. Nihilisitc intellgetsia is ignorant and often dumb. Intelligentsia accuses Soviet union in crimes that are common to all states and all economic systems. Their ignorance leads them to equate their nihilism with democracy.”

In one of this articles from 1990, Limonov concedes that Gorbachev was honest and well-meaning, even if soft. Gorbachev wanted to de-Stalinize the USSR — to bring “socialism with a human face”. But he was also a provincial country bumpkin, “the first generation in his family to get a higher education, a person who joined the Communist Party aquarium early in life”. Decades before Vladislav Zubok’s recent, influential book Collapse, Limonov described Gorbachev in very much the same way: as very naive and ignorant about how about western democracies worked and about how power worked in a complex and fragile society like the USSR. I’d add that it’s no wonder Gorbachev ended up defeated, dethroned, and in a Pizza Hut commercial.

As Limonov explains, much of Soviet intelligentsia — along with a part of the Communist Party aristocracy like Gorbachev — were on a self-flagellation binge. It was masochistic and inane, since Khrushchev already denounced Stalin in 1956, three years after leader’s death. So this new wave of perestroika’s public humiliation ritual was excessive and dangerous, as Limonov writes. No left intellectuals — let alone anyone in power — in France or America would go that far denouncing their own country into extinction and suicide, in the name of reform. If the USSR is so uniquely evil, why would you even want to keep it reformed?

What I find fascinating about Limonov’s essays is that they were written right as history was being made in real time and widely published. He was right about most things. And yet he had no real effect on politics — at least not right away. Looking at it now, it’s clear how darkly prophetic he was about the outcome of this dismantling. Back in the early 90s most Russian “democrats” called him fascist for doubting the utter evil of the USSR.

In 1984 Limonov published a short sci-fi story in the French magazine Zolou. This essay collection takes its title from it — the “Disappearance of the Barbarians”. Despite the story being rather crude, it’s very accurate politically. It’s a story about a world where the Soviet Union one day just disappeared and only white gypsum remained on its whole huge surface. This led western countries to freak out — losing an enemy wasn’t in their interest. They needed it to function to have big military budgets, to scare their population into submission, etc. So they tried to covertly convince China to become their official enemy, but their leader declined and said they’d gladly give in to Americans (but secretly the Chinese plotted to just assimilate the Americans like they did with the Mongols). So the West felt hopeless. It needed the Soviet Union or Russia or whatever you want to call it. It needed “the other” to maintain its own power structure and lamented its lack. And it’s that exactly what ended up happening? After the collapse of the USSR, America couldn’t really deal with not having an enemy any more. So it invented the War on Terror but then that wasn’t nearly enough — you needed an equal foe to prop up such a giant corrupt military machine.

And so Russia began to be invented as a threat — with Bush and Obama and Biden and Trump all ramping up a New Cold War. It shows how prophetic Limonov was in this short story. Blaming the external enemy for all the world’s problems — and at the same time requiring this external enemy for internal stability — is the modus operandi of the American empire.

The New Cold War as predicted by Limonov in the late 1980s is not ideological — Russia is not socialist and doesn’t offer an alternative economic system or set of values. The Cold War now is purely geopolitical and this time all masks are down. Hungry for power and resources, the American Empire can’t really hide its motifs anymore behind the usual tired slogans— “freedom, liberty, democracy”.

Among Limonov’s predictions that came true was nationalism being back in trend again. He wrote that since the supra-nationalist ideology of the USSR was no more, violent nationalism of former Soviet Republic would be easily ignited. He writes “Ukrainian nationalism can easily ignite and wake up Russian nationalism”.

He wrote:

“I visited the USSR in December 1989, and the country looked scary, horrifying — crimes, nationalistic uprisings, ethnic massacres, strikes are raging across the country, and the economy is worse than before perestroika, and there is no sign that it’ll be any better soon. When I left the USSR in 1974, the country was in a better state, and Soviet people looked happier and calmer.”

In the end, he saw that perestroika would lead down a dark path because it was naive and simpleminded, not taking into account the complexity and cynicism of the world as it exists. He explicitly called perestroika’s “one-sided altruism” dangerous and referred to it as a phenomenon as “Chaadevshina,” a term he coined using the name of the famous nobleman, traveller, and philosopher Pyotr Chaadayev, who saw Russia as backwards and infinitely inferior compared to an “enlightened Europe”.

As Limonov wrote:

“Altruism is great if everyone is engaged in it, and all other states and nations undergo their own perestroikas. But this is not the case — in fact, it’s the opposite — the Western heads of states stole the legacy of Soviet perestroika and claim that the democratization in Eastern Europe is the sign of victory for capitalism over communism.”

I think because of Limonov’s poetic gift (people forget that he was first and foremost a poet), Limonov can be very astute in his political articles. He comes up with terms that I never saw any liberal Russian journalist or politician ever use. These terms help to make sense of what actually happened in the USSR.

For instance, Limonov calls old Communist Party leaders — “communist aristocracy,” and he calls the upheaval of the early 90s a “true bourgeois revolution”, rather than a conflict between the democratic reformers and communist conservatives or as freedom vs. totalitarianism, as Westerners or Russian liberals described it.

In many ways, Russia in 1991 did undergo a version of the 1917 February Revolution, and the revolution did stick this time around. The irony is that it was made by former (as I call them) ambitious, cruel peasants turned into Communist Party-adjacent apparatchiks, who privatized whatever chunk of the Soviet Union they could get their hands on the moment it became possible. There were no Milukovs or Nabokovs in this belated bourgeois revolution — meaning no one out of the beneficiaries of the collapse really believed in the noble aims of the bourgeois revolution they were leading. TK, okay? They were just grabbing and stealing what they could. They had nothing to offer society, other than that. As Limonov writes, the main trick of this new bourgeoisie was to appeal to the crimes of the past — to things like Stalinism and to Soviet stagnation — in order to take power away and discredit the communist aristocracy.

Eventually, in the late 90s, came the disillusionment with this bourgeois counter-revolution — the same way that the disillusionment with the Bolshevik revolution was quite apparent by the late 1920s.

As Limonov wrote:

“Anticollectivisation of the 1990s turned out as painful as the collectivization of the 1920s. It undid the whole psychological way of life and made it obsolete, meaningless for tens of millions of people.

In an article from 1991, Limonov was shocked by what he saw around himself in Moscow. He described it as “unnecessary masochism”. To him, it was strange to watch the USSR doing penance, even as the USA was entering a phase of “militarist self-aggrandizing glory” in response. This was not the reaction of a friend. It was clear to him that no matter how much the USSR self-flagellated, America would not help Russia gain prosperity and freedom for its people, and it was idiotic and naive for Russian politicians to believe that it would.

Limonov predicted that the Russian penance period would end badly — and it did. And now Russia is in its self-aggrandizing militarism phase. But who is there to blame?