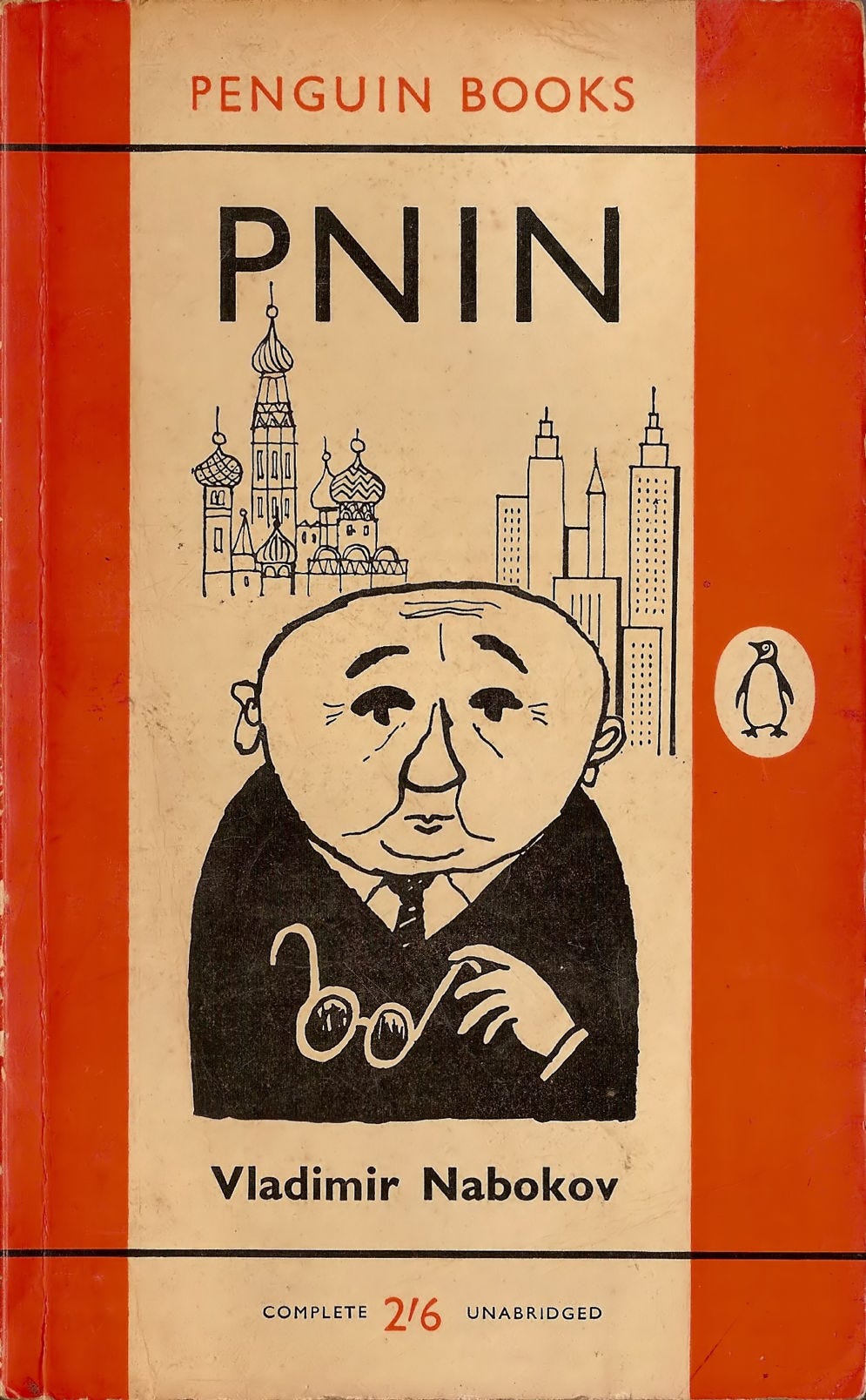

Nabokov’s "Pnin"

I just finished reading Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin, a semi-autobiographical novel about a sad Russian emigre curmudgeon academic — based on his experience teaching in America and all the time he spent among the hordes of “cultured” White Russian emigres that suddenly swamped western institutions of higher learning after the Russian Revolution.

Source

Pnin starts out slow, but grows on you as you keep slogging through it. One thing about Nabokov is that he absolutely resented American academia and the polite and genteel provincialism of the people who populated that world. But he also hated his own people, the ragtag impoverished emigres who tried clinging to their old notions of upper crust privilege and culture and put on refined airs about being poets and novelists and thinkers in “salons” in Berlin and Paris — “literary soirees where young émigré poets, who had left Russia in their pale, unpampered pubescence, chanted nostalgic elegies dedicated to a country that could be little more to them than a sad stylized toy, a bauble found in the attic, a crystal globe which you shake to make a soft luminous snowstorm inside over a minuscule fir tree and a log cabin of papier mâché.”

But as much as Nabokov might have disliked parts of that Russian emigre world, he was a part of it and thought it had real value. And he resented that no one in American academia knew about it — let alone thought that it had anything to offer the world.

…I saw Pnin and her at an evening tea in the apartment of a famous émigré, a social revolutionary, one of those informal gatherings where old-fashioned terrorists, heroic nuns, gifted hedonists, liberals, adventurous young poets, elderly novelists and artists, publishers and publicists, free-minded philosophers and scholars would represent a kind of special knighthood, the active and significant nucleus of an exiled society which during the third of a century it flourished remained practically unknown to American intellectuals, for whom the notion of Russian emigration was made to mean by astute communist propaganda a vague and perfectly fictitious mass of so-called Trotskiites (whatever these are), ruined reactionaries, reformed or disguised Cheka men, titled ladies, professional priests, restaurant keepers, and White Russian military groups, all of them of no cultural importance whatever.

I gotta admit that I myself must also have been victim of this “astute communist propaganda” because I too tend to oversimplify that world. First Wave Russian immigrants? They’re all reactionary to me!

Anyway, Nabokov hated everyone equally. He hated his own people and he hated the people of his adopted homeland. And as a fellow immigrant, I respect that. It’s the right, healthy approach to life. But you don’t see much of it these days.

—Yasha Levine

This is a free newsletter. Subscribe to get full access.

kinda think this problem is common to all the European cultures destroyed by the wars of the 20th century. The brain drain that followed gave America a chance to integrate sophisticated European traditions but we fumbled.

Integration failed because we are essentially an odd collection of bumpkins and imperialists. Foreign cultures, if not mistrusted outright, are fed into a process of aggressive assimilation.

The soil here is barren; nothing of value survives.